2017 SeqGANSequenceGenerativeAdversa

- (Yu, Zhang et al., 2017) ⇒ Lantao Yu, Weinan Zhang, Jun Wang, and Yong Yu. (2017). “SeqGAN: Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets with Policy Gradient.” In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2017).

Subject Headings: SeqGAN, Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), Generative Model, Discriminative Model, Oracle Generated Log-Likelihood Measure.

Notes

- Version(s) and URL(s):

Cited By

- Google Scholar: ~ 950 Citations.

- Semantic Scholar: ~ 911 Citations.

- MS Academic: ~ 862 Citations.

Quotes

Author Keyworks

Abstract

As a new way of training generative models, Generative Adversarial Net (GAN) that uses a discriminative model to guide the training of the generative model has enjoyed considerable success in generating real-valued data. However, it has limitations when the goal is for generating sequences of discrete tokens. A major reason lies in that the discrete outputs from the generative model make it difficult to pass the gradient update from the discriminative model to the generative model. Also, the discriminative model can only assess a complete sequence, while for a partially generated sequence, it is non-trivial to balance its current score and the future one once the entire sequence has been generated. In this paper, we propose a sequence generation framework, called SeqGAN, to solve the problems. Modeling the data generator as a stochastic policy in reinforcement learning (RL), SeqGAN bypasses the generator differentiation problem by directly performing gradient policy update. The RL reward signal comes from the GAN discriminator judged on a complete sequence, and is passed back to the intermediate state-action steps using Monte Carlo search. Extensive experiments on synthetic data and real-world tasks demonstrate significant improvements over strong baselines.

Introduction

Generating sequential synthetic data that mimics the real one is an important problem in unsupervised learning. Recently, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with long short-term memory (LSTM) cells (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997) have shown excellent performance ranging from natural language generation to handwriting generation (Wen et al. 2015; Graves 2013). The most common approach to training an RNN is to maximize the log predictive likelihood of each true token in the training sequence given the previous observed tokens (Salakhutdinov 2009). However, as argued in (Bengio et al. 2015), the maximum likelihood approaches suffer from so-called exposure bias in the inference stage: the model generates a sequence iteratively and predicts next token conditioned on its previously predicted ones that may be never observed in the training data. Such a discrepancy between training and inference can incur accumulatively along with the sequence and will become prominent as the length of sequence increases. To address this problem, (Bengio et al. 2015) proposed a training strategy called scheduled sampling (SS), where the generative model is partially fed with its own synthetic data as prefix (observed tokens) rather than the true data when deciding the next token in the training stage. Nevertheless, (Huszar 2015) showed that SS is an inconsistent training strategy and fails to address the problem fundamentally. Another possible solution of the training/inference discrepancy problem is to build the loss function on the entire generated sequence instead of each transition. For instance, in the application of machine translation, a task specific sequence score/loss, bilingual evaluation understudy (BLEU) (Papineni et al. 2002), can be adopted to guide the sequence generation. However, in many other practical applications, such as poem generation (Zhang and Lapata 2014) and chatbot (Hingston 2009), a task specific loss may not be directly available to score a generated sequence accurately.

General adversarial net (GAN) proposed by (Goodfellow and others 2014) is a promising framework for alleviating the above problem. Specifically, in GAN a discriminative net $D$ learns to distinguish whether a given data instance is real or not, and a generative net $G$ learns to confuse $D$ by generating high quality data. This approach has been successful and been mostly applied in computer vision tasks of generating samples of natural images (Denton et al. 2015).

Unfortunately, applying GAN to generating sequences has two problems. Firstly, GAN is designed for generating real valued, continuous data but has difficulties in directly generating sequences of discrete tokens, such as texts (Huszar 2015). The reason is that in GANs, the generator starts with random sampling first and then a determistic transform, governmented by the model parameters. As such, the gradient of the loss from $D$ w.r.t. the outputs by $G$ is used to guide the generative model $G$ (parameters) to slightly change the generated value to make it more realistic. If the generated data is based on discrete tokens, the “slight change” guidance from the discriminative net makes little sense because there is probably no corresponding token for such slight change in the limited dictionary space (Goodfellow 2016). Secondly, GAN can only give the score/loss for an entire sequence when it has been generated; for a partially generated sequence, it is non-trivial to balance how good as it is now and the future score as the entire sequence.

In this paper, to address the above two issues, we follow (Bachman and Precup 2015; Bahdanau et al. 2016) and consider the sequence generation procedure as a sequential decision making process. The generative model is treated as an agent of reinforcement learning (RL); the state is the generated tokens so far and the action is the next token to be generated. Unlike the work in (Bahdanau et al. 2016) that requires a task-specific sequence score, such as BLEU in machine translation, to give the reward, we employ a discriminator to evaluate the sequence and feedback the evaluation to guide the learning of the generative model. To solve the problem that the gradient cannot pass back to the generative model when the output is discrete, we regard the generative model as a stochastic parametrized policy. In our policy gradient, we employ Monte Carlo (MC) search to approximate the state-action value. We directly train the policy (generative model) via policy gradient (Sutton et al. 1999), which naturally avoids the differentiation difficulty for discrete data in a conventional GAN.

Extensive experiments based on synthetic and real data are conducted to investigate the efficacy and properties of the proposed SeqGAN. In our synthetic data environment, SeqGAN significantly outperforms the maximum likelihood methods, scheduled sampling and PG-BLEU. In three real world tasks, i.e. poem generation, speech language generation and music generation, SeqGAN significantly outperforms the compared baselines in various metrics including human expert judgement.

Related Work

Deep generative models have recently drawn significant attention, and the ability of learning over large (unlabeled) data endows them with more potential and vitality (Salakhutdinov 2009; Bengio et al. 2013). (Hinton, Osindero, and Teh 2006) first proposed to use the contrastive divergence algorithm to efficiently training deep belief nets (DBN). (Bengio et al. 2013) proposed denoising autoencoder (DAE) that learns the data distribution in a supervised learning fashion. Both DBN and DAE learn a low dimensional representation (encoding) for each data instance and generate it from a decoding network. Recently, variational autoencoder (VAE) that combines deep learning with statistical inference intended to represent a data instance in a latent hidden space (Kingma and Welling 2014), while still utilizing (deep) neural networks for nonlinear mapping. The inference is done via variational methods. All these generative models are trained by maximizing (the lower bound of) training data likelihood, which, as mentioned by (Goodfellow and others 2014), suffers from the difficulty of approximating intractable probabilistic computations. (Goodfellow and others 2014) proposed an alternative training methodology to generative models, i.e. GANs, where the training procedure is a minimax game between a generative model and a discriminative model. This framework bypasses the difficulty of maximum likelihood learning and has gained striking successes in natural image generation (Denton et al. 2015). However, little progress has been made in applying GANs to sequence discrete data generation problems, e.g. natural language generation (Huszar 2015). This is due to the generator network in GAN is designed to be able to adjust the output continuously, which does not work on discrete data generation (Goodfellow 2016).

On the other hand, a lot of efforts have been made to generate structured sequences. Recurrent neural networks can be trained to produce sequences of tokens in many applications such as machine translation (Sutskever, Vinyals, and Le 2014; Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014). The most popular way of training RNNs is to maximize the likelihood of each token in the training data whereas (Bengio et al. 2015) pointed out that the discrepancy between training and generating makes the maximum likelihood estimation suboptimal and proposed scheduled sampling strategy (SS). Later (Huszar 2015) theorized that the objective function underneath SS is improper and explained the reason why GANs tend to generate natural-looking samples in theory. Consequently, the GANs have great potential but are not practically feasible to discrete probabilistic models currently.

As pointed out by (Bachman and Precup 2015), the sequence data generation can be formulated as a sequential decision making process, which can be potentially be solved by reinforcement learning techniques. Modeling the sequence generator as a policy of picking the next token, policy gradient methods (Sutton et al. 1999) can be adopted to optimize the generator once there is an (implicit) reward function to guide the policy. For most practical sequence generation tasks, e.g. machine translation (Sutskever, Vinyals, and Le 2014), the reward signal is meaningful only for the entire sequence, for instance in the game of Go (Silver et al. 2016), the reward signal is only set at the end of the game. In those cases, state-action evaluation methods such as Monte Carlo (tree) search have been adopted (Browne et al. 2012). By contract, our proposed SeqGAN extends GANs with the RL-based generator to solve the sequence generation problem, where a reward signal is provided by the discriminator at the end of each episode via Monte Carlo approach, and the generator picks the action and learns the policy using estimated overall rewards.

Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets

The sequence generation problem is denoted as follows. Given a dataset of real-world structured sequences, train a $\theta$-parameterized generative model $G_{\theta}$ to produce a sequence $Y_{1:T} = \left(y_1,\cdots, y_t,\cdots, y_T\right), y_t \in \mathcal{Y}$, where $\mathcal{Y}$ is the vocabulary of candidate tokens. We interpret this problem based on reinforcement learning. In timestep $t$, the state $s$ is the current produced tokens $\left(y_1,\cdots, y_{t—1}\right)$ and the action a is the next token $y_t$ to select. Thus the policy model $G_{\theta} \left(y_t|Y_{1:t-1}\right)$ is stochastic, whereas the state transition is deterministic after an action has been chosen, i.e. $\delta^a_{s,s'} = 1$ for the next state $s' = Y_{1:t}$ if the current state $s = Y_{1:t-1}$ and the action $a = y_t$ for other next states $s^{"}$, $\delta^{a}_{s,s^{"}} = 0$.

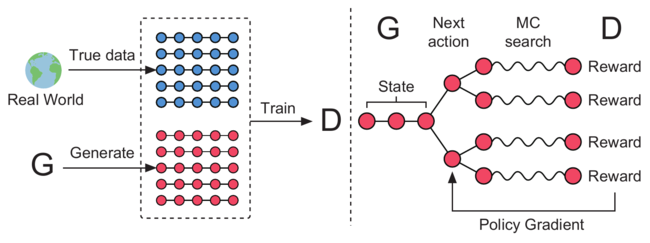

Additionally, we also train a $\phi$-parameterized discriminative model $D_{\phi}$ (Goodfellow and others 2014) to provide a guidance for improving generator $G_{\theta}$. $D_{\phi}(Y_{1:T})$ is a probability indicating how likely a sequence $Y_{1:T}$ is from real sequence data or not. As illustrated in Figure 1, the discriminative model $D_{\phi}$ is trained by providing positive examples from the real sequence data and negative examples from the synthetic sequences generated from the generative model $G_{\theta}$. At the same time, the generative model $G_{\theta}$ is updated by employing a policy gradient and MC search on the basis of the expected end reward received from the discriminative model $D_{\phi}$. The reward is estimated by the likelihood that it would fool the discriminative model $D_{\phi}$. The specific formulation is given in the next subsection.

|

SeqGAN via Policy Gradient

Following (Sutton et al. 1999), when there is no intermediate reward, the objective of the generator model (policy) $G_{\theta}\left(y_t|Y_{1:t-1}\right)$ is to generate a sequence from the start state $s_0$ to maximize its expected end reward:

| [math]\displaystyle{ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}\big[R_T\vert s_0,\theta \big] = \sum_{y_1\in\mathcal{Y}} G_{\theta}\left(y_1\vert s_9\right) \cdot Q_{D_{\phi}}^{G_{\theta}} \left(s_0, y_1\right) }[/math] | (1) |

where $R_T$ is the reward for a complete sequence. Note that the reward is from the discriminator $D_{\phi}$, which we will discuss later. $Q^{G_{\theta}}_{D_{\phi}} \left(s,a\right)$ is the action-value function of a sequence, i.e. the expected accumulative reward starting from state $s$, taking action $a$, and then following policy $G_{\theta}$. The rational of the objective function for a sequence is that starting from a given initial state, the goal of the generator is to generate a sequence which would make the discriminator consider it is real.

The next question is how to estimate the action-value function. In this paper, we use the REINFORCE algorithm (Williams 1992) and consider the estimated probability of being real by the discriminator $D_{\phi}\left(Y^n_{1:T}\right)$ as the reward. Formally, we have:

| [math]\displaystyle{ Q_{D_{\phi}}^{G_{\theta}} \left(a = y_T, S = Y_{1:T-1}\right) = D_{\phi}\left(Y_{1:T}\right) }[/math], | (2) |

However, the discriminator only provides a reward value for a finished sequence. Since we actually care about the long-term reward, at every timestep, we should not only consider the fitness of previous tokens (prefix) but also the resulted future outcome. This is similar to playing the games such asGo or Chess where players sometimes would give up the immediate interests for the long-term victory (Silver et al. 2016). Thus, to evaluate the action-value for an intermediate state, we apply Monte Carlo search with a roll-out policy $G_{beta}$ to sample the unknown last $T—t$ tokens. We represent an $N$-time Monte Carlo search as

| [math]\displaystyle{ \{Y^1_{1:T},...Y^N_{1:T}\} = MC^{G_{\beta}} (Y1:4;.N) }[/math], | (3) |

where $Y^n_{1:t} = \left(y_1,\cdots, y_t\right)$ and $Y^n_{t+1:T}$ is sampled based on the roll-out policy $G_{\beta}$ and the current state. In our experiment, $G_{\beta}$ is set the same as the generator, but one can use a simplified version if the speed is the priority (Silver et al. 2016). To reduce the variance and get more accurate assessment of the action value, we run the roll-out policy starting from current state till the end of the sequence for $N$ times to get a batch of output samples. Thus, we have:

| [math]\displaystyle{ Q^{G_{\theta}}_{D_{\phi}}\left(s=Y_{1:t-1},a=y_t\right) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} D_{\phi}\left(Y^n_{1:T}\right), Y^n_{1:T} \in MC^{G\beta} \left(Y_{1:t}:N\right) & \mbox{for } t\lt T \\ D_{\phi}\left(Y_{1:t}\right) & \mbox{for } t=T \end{cases} }[/math] | (4) |

where, we see that when no intermediate reward, the function is iteratively defined as the next-state value starting from state $s’ = Y_{1:t}$, and rolling out to the end.

A benefit of using the discriminator $D_{\phi}$ as a reward function is that it can be dynamically updated to further improve the generative model iteratively. Once we have a set of more realistic generated sequences, we shall re-train the discriminator model as follows:

| [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{\phi}{min} —\mathbb{E}_{Y\sim p_{data}} \big[log D_{\phi}(Y)\big] — \mathbb{E}_{Y\sim G_{\theta}}\big[\log\left(1— D_{\phi}\left(Y\right)\right)\big] }[/math], | (5) |

Each time when a new discriminator model has been obtained, we are ready to update the generator. The proposed policy based method relies upon optimizing a parametrized policy to directly maximize the long-term reward. Following (Sutton et al. 1999), the gradient of the objective function $J\left(\theta\right)$ w.r.t. the generator’s parameters $\theta$ can be derived as

| [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_{\theta}J\left(\theta\right) =\mathbb{E}_{y_{1:t-1}}\sim G_{\theta}\big[\displaystyle \sum_{y_t\in \mathcal{Y}} \nabla_{\theta}G_{\theta}\left(y_t|Y_{1:t—1}\right)\cdot Q^{G_{\theta}}_{D_{\theta}}\cdot (Y_{1:t-1}, y_t)\big] }[/math]. | (6) |

The above form is due to the deterministic state transition and zero intermediate rewards. The detailed derivation is provided in the supplementary material[1]. Using likelihood ratios (Glynn 1990; Sutton et al. 1999), we build an unbiased estimation for Eq. (6) (on one episode):

| [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_{\theta}J\left(\theta\right) \simeq \dfrac{1}{T}\displaystyle\sum^T_{t=1} \sum_{y_t \in \mathcal{Y}} \nabla_{\theta}G_{\theta}\left(y_t|Y_{1:t−1}\right) \cdot Q^{G_{\theta}}_{D_{\phi}} \left(Y_{1:t−1}, y_t\right) }[/math] | (7) |

| [math]\displaystyle{ = \dfrac{1}{T} \displaystyle\sum^T_{t=1} \sum_{y_t \in \mathcal{Y}} G_{\theta}\left(y_t|Y_{1:t−1}\right)\nabla_{\theta} \log G_{\theta}\left(y_t|Y_{1:t−1}\right) \cdot Q^{G_{\theta}}_{D_{\phi}} \left(Y_{1:t−1}, y_t\right) }[/math] | |

| [math]\displaystyle{ = \dfrac{1}{T} \displaystyle\sum^T_{t=1} \mathbb{E}_{y_t\sim G_{\theta}\left(yt |Y_{1:t−1}\right)}\big[\nabla_{\theta} \log G_{\theta}\left(y_t\vert Y_{1:t−1}\right) \cdot Q^{G_{\theta}}D_{\phi} \left(Y_{1:t−1}, y_t\right)\big] }[/math], | |

where $Y_{1:t—1}$ 1s the observed intermediate state sampled from $G_{\theta}$. Since the expectation $\mathbb{E[\cdot]}$ can be approximated by sampling methods, we then update the generator’s parameters as:

| [math]\displaystyle{ \theta \gets \theta + \alpha_h\nabla_{\theta}J(\theta) }[/math], | (8) |

where $\alpha_{h} \in R^+$ denotes the corresponding learning rate at $h$-th step. Also the advanced gradient algorithms such as Adam and RMSprop can be adopted here.

In summary, Algorithm 1 shows full details of the proposed SeqGAN. At the beginning of the training, we use the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to pre-train $G_{\theta}$ on training set $S$. We found the supervised signal from the pre-trained discriminator is informative to help adjust the generator efficiently.

After the pre-training, the generator and discriminator are trained alternatively. As the generator gets progressed via training on g-steps updates, the discriminator needs to be re- trained periodically to keeps a good pace with the generator. When training the discriminator, positive examples are from the given dataset $\mathcal{S}$, whereas negative examples are generated from our generator. In order to keep the balance, the number of negative examples we generate for each d-step is the same as the positive examples. And to reduce the variability of the estimation, we use different sets of negative samples combined with positive ones, which is similar to bootstrapping (Quinlan 1996).

{|class="wikitable" style="border:1px solid black;border-spacing:1px; background-color:white; text-align:left; margin:1em auto; width: 70%"

|- !style="text-align:left"|Algorithm 1 Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets |- |Require: generator policy $G_{\theta}$; roll-out policy $G_{\beta}$; discriminator $D_{\phi}$; a sequence dataset $\mathcal{S} = \{X_{1:T}\}$ |-

|1: Initialize $G_{\theta}$, $D_{\phi}$ with random weights $\theta$, $\phi$.

2: Pre-train $G_{\theta}$ using MLE on $\mathcal{S}$

3: $\beta \gets \theta$

4: Generate negative samples using $G_{\theta}$ for training $D_{\phi}$

5: Pre-train $D_{\phi}$ via minimizing the cross entropy

6: repeat

7: for g-steps do

8: Generate a sequence $Y_{1:T} = \left(y_1, \cdots , y_T \right) \sim G_{\theta}$

9: for $t$ in $1 : T$ do

10: Compute $Q\left(a = y_t; s = Y_{1:t−1}\right)$ by Eq. (4)

11: end for

12: Update generator parameters via policy gradient Eq. (8)

13: end for

14: for d-steps do

15: Use current $G_{\theta}$ to generate negative examples and combine with given positive examples $\mathcal{S}$

16: Train discriminator $D_{\phi}$ for $k$ epochs by Eq. (5)

17: end for

18: $\beta \gets \theta$

19: until SeqGAN converges |- |}

The Generative Model for Sequences

We use recurrent neural networks (RNNs) (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997) as the generative model. An RNN maps the input embedding representations $x_1,\cdots, x_T$ of the sequence $x_1,\cdots,x_T$ into a sequence of hidden states $h_1,\cdots,h_T$ by using the update function $g$ recursively.

| [math]\displaystyle{ h_t = g\left(h_{t-1}, x_t\right) }[/math], | (9) |

Moreover, a softmax output layer $z$ maps the hidden states into the output token distribution

| [math]\displaystyle{ p\left(y_t|x_1,\cdots, x_t\right) = 2\left(h_t\right) = \mathrm{softmax}\left(c + Vh_t\right) }[/math], | (10) |

where the parameters are a bias vector $c$ and a weight matrix $V$. To deal with the common vanishing and exploding gradient problem (Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville 2016) of the backpropagation through time, we leverage the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cells (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997) to implement the update function $g$ in Eq. (9). It is worth noticing that most of the RNN variants, such as the gated recurrent unit (GRU) (Cho et al. 2014) and soft attention mechanism (Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014), can be used as a generator in SeqGAN.

The Discriminative Model for Sequences

Deep discriminative models such as deep neural network (DNN) (Vesely et al. 2013), convolutional neural network (CNN) (Kim 2014) and recurrent convolutional neural network (RCNN) (Lai et al. 2015) have shown a high performance in complicated sequence classification tasks. In this paper, we choose the CNN as our discriminator as CNN has recently been shown of great effectiveness in text (token sequence) classification (Zhang and LeCun 2015). Most discriminative models can only perform classification well for an entire sequence rather than the unfinished one. In this paper, we also focus on the situation where the discriminator predicts the probability that a finished sequence is real[2].

We first represent an input sequence $x_1,\cdots, x_T$ as:

| [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_{1:T} = x_1 \oplus x_2 \oplus \cdots \oplus x_T }[/math], | (11) |

where $x_t \in R^k$ is the k-dimensional token embedding and $\oplus$ is the concatenation operator to build the matrix $\varepsilon_{1:T} \in \mathbb{R}^{T\times k}$. Then a kernel $w \in R^{l\times k}$ applies a convolutional operation to a window size of $l$ words to produce a new feature map:

| [math]\displaystyle{ c_i = \rho(w \otimes \varepsilon_{i:i+l-1} + b) }[/math], | (12) |

where $\otimes$ operator is the summation of elementwise production, $b$ is a bias term and $p$ is a non-linear function. We can use various numbers of kernels with different window sizes to extract different features. Finally we apply a max-over-time pooling operation over the feature maps $\tilde{c}=\mathrm{max}\{c_1,\cdots,c_{T—l+1}\}$.

To enhance the performance, we also add the highway architecture (Srivastava, Greff, and Schmidhuber 2015) based on the pooled feature maps. Finally, a fully connected layer with sigmoid activation is used to output the probability that the input sequence is real. The optimization target is to minimize the cross entropy between the ground truth label and the predicted probability as formulated in Eq. (5).

Detailed implementations of the generative and discriminative models are provided in the supplementary material.

Synthetic Data Experiments

To test the efficacy and add our understanding of SeqGAN, we conduct a simulated test with synthetic data[3]. To simulate the real-world structured sequences, we consider a language model to capture the dependency of the tokens. We use a randomly initialized LSTM as the true model, aka, the oracle, to generate the real data distribution $p\left(x_t|x_1, \cdots , x_{t−1}\right)$ for the following experiments.

Evaluation Metric

The benefit of having such oracle is that firstly, it provides the training dataset and secondly evaluates the exact performance of the generative models, which will not be possible with real data. We know that MLE is trying to minimize the cross-entropy between the true data distribution $p$ and our approximation $q$, i.e. $—\mathbb{E}_{x\sim p}\log q(x)$. However, the most accurate way of evaluating generative models is that we draw some samples from it and let human observers review them based on their prior knowledge. We assume that the human observer has learned an accurate model of the natural distribution $P_{human}(x)$. Then in order to increase the chance of passing Turing Test, we actually need to minimize the exact opposite average negative log-likelihood $—\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p} \log p_{human}(x)$ (Huszar 2015), with the role of $p$ and $q$ exchanged. In our synthetic data experiments, we can consider the oracle to be the human observer for real-world problems, thus a perfect evaluation metric should be

| [math]\displaystyle{ NLL_{oracle} = —\mathbb{E}_{1:T}\sim G_{\theta} \big[\sum^T_{t=1}\log G_{oracle} \left(Y_t | Y_{1:t-1}\right)\big] }[/math], | (13) |

where $G_{\theta}$ and $G_{oracle}$ denote our generative model and the oracle respectively.

At the test stage, we use $G_{\theta}$ to generate 100,000 sequence samples and calculate $NLL_{oracle}$ for each sample by $G_{oracle}$ and their average score. Also significance tests are performed to compare the statistical properties of the generation performance between the baselines and SeqGAN.

Training Setting

To set up the synthetic data experiments, we first initialize the parameters of an LSTM network following the normal distribution $\mathcal{N}\left(0, 1\right)$ as the oracle describing the real data distribution $G_{oracle}\left(x_1|x_1,\cdots,x_{t—1}\right)$. Then we use it to generate 10,000 sequences of length 20 as the training set $\mathcal{S}$ for the generative models.

In SeqGAN algorithm, the training set for the discriminator is comprised by the generated examples with the label 0 and the instances from $\mathcal{S}$ with the label 1. For different tasks, one should design specific structure for the convolutional layer and in our synthetic data experiments, the kernel size is from 1 to $T$ and the number of each kernel size is between 100 to 200[4]. Dropout (Srivastava et al. 2014) and L2 regularization are used to avoid over-fitting.

Four generative models are compared with SeqGAN. The first model is a random token generation. The second one is the MLE trained LSTM $G_{\theta}$. The third one is scheduled sampling (Bengio et al. 2015). The fourth one is the Policy Gradient with BLEU (PG-BLEU). In the scheduled sampling, the training process gradually changes from a fully guided scheme feeding the true previous tokens into LSTM, towards a less guided scheme which mostly feeds the LSTM with its generated tokens. A curriculum rate w is used to control the probability of replacing the true tokens with the generated ones. To get a good and stable performance, we decrease w by 0.002 for every training epoch. In the PG-BLEU algorithm, we use BLEU, a metric measuring the similarity between a generated sequence and references (training data), to score the finished samples from Monte Carlo search.

Results

The $NLL_{oracle}$ performance of generating sequences from the compared policies is provided in Table 1. Since the evaluation metric is fundamentally instructive, we can see the impact of SeqGAN, which outperforms other baselines significantly. A significance T-test on the $NLL_{oracle}$ score distribution of the generated sequences from the compared models is also performed, which demonstrates the significant improvement of SeqGAN over all compared models.

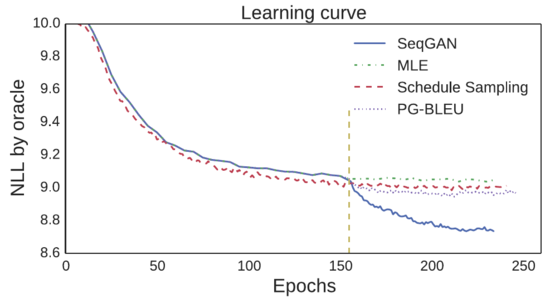

The learning curves shown in Figure 2 illustrate the superiority of SeqGAN explicitly. After about 150 training epochs, both the maximum likelihood estimation and the schedule sampling methods converge to a relatively high $NLL_{oracle}$ score, whereas SeqGAN can improve the limit of the generator with the same structure as the baselines significantly. This indicates the prospect of applying adversarial training strategies to discrete sequence generative models to breakthrough the limitations of MLE. Additionally, SeqGAN outperforms PG-BLEU, which means the discriminative signal in GAN is more general and effective than a predefined score (e.g. BLEU) to guide the generative policy to capture the underlying distribution of the sequence data.

{|class="wikitable" style="border:1px solid black;border-spacing:1px; text-align:center; background-color:white; margin:1em auto; width:90%" |- !Algorithm!! Random !!MLE !!SS!!PG-BLEU!!SeqGAN |- !NLL |10.310|| 9.038|| 8.985|| 8.946|| 8.736 |- !p-value |$< 10^{−6}$|| $< 10^{−6}$|| $< 10^{−6}$|| $< 10^{−6}$|| |- |+ align="bottom" style="caption-side:top; text-align:left; font-weight:normal"|Table 1: Sequence generation performance comparison. The p-value is between SeqGAN and the baseline from T-test. |}

|

Discussion

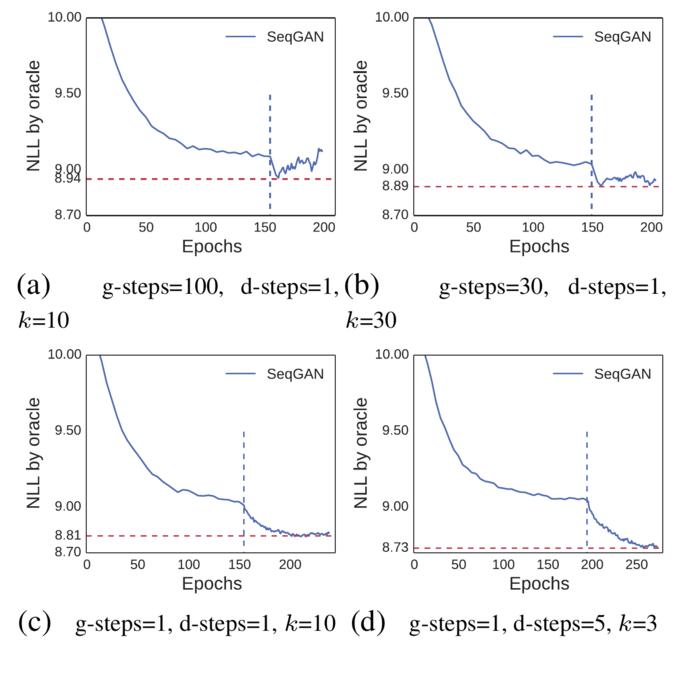

In our synthetic data experiments, we find that the stability of SeqGAN depends on the training strategy. More specifically, the g-steps, d-steps and k parameters in Algorithm 1 have a large effect on the convergence and performance of SeqGAN. Figure 3 shows the effect of these parameters. In Figure 3(a), the g-steps is much larger than the d-steps and epoch number $k$, which means we train the generator for many times until we update the discriminator. This strategy leads to a fast convergence but as the generator improves quickly, the discriminator cannot get fully trained and thus will provide a misleading signal gradually. In Figure 3 (b), with more discriminator training epochs, the unstable training process is alleviated. In Figure 3 (c), we train the generator for only one epoch and then before the discriminator gets fooled, we update it immediately based on the more realistic negative examples. In such a case, SeqGAN learns stably.

The d-steps in all three training strategies described above is set to 1, which means we only generate one set of negative examples with the same number as the given dataset, and then train the discriminator on it for various $k$ epochs. But actually we can utilize the potentially unlimited number of negative examples to improve the discriminator. This trick can be considered as a type of bootstrapping, where we combine the fixed positive examples with different negative examples to obtain multiple training sets. Figure 3 (d) shows this technique can improve the overall performance with good stability, since the discriminator is shown more negative examples and each time the positive examples are emphasized, which will lead to a more comprehensive guidance for training generator. This is in line with the theorem in (Goodfellow and others 2014). When analyzing the convergence of generative adversarial nets, an important assumption is that the discriminator is allowed to reach its optimum given G. Only if the discriminator is capable of differentiating real data from unnatural data consistently, the supervised signal from it can be meaningful and the whole adversarial training process can be stable and effective.

|

Real-world Scenarios

To complement the previous experiments, we also test SeqGAN on several real-world tasks, i.e. poem composition, speech language generation and music generation.

Text Generation

For text generation scenario s, we apply the proposed SeqGAN to generate Chinese poem s and Barack Obama political speeches. In the poem composition task, we use a corpus [5] of 16,394 Chinese quatrain $s$, each containing four lines of twenty characters in total. To focus on a fully automatic solution and stay general, we did not use any prior knowledge of special structure rules in Chinese poems such as specific phonological rules. In the Obama political speech generation task, we use a corpus[6], which is a collection of 11,092 paragraphs from Obama's political speeches.

We use BLEU score as an evaluation metric to measure the similarity degree between the generated texts and the human-created texts. BLEU is originally designed to automatically judge the machine translation quality (Papineni et al. 2002). The key point is to compare the similarity between the results created by machine and the references provided by human. Specifically, for poem evaluation, we set n-gram to be 2 (BLEU-2) since most words (dependency) in classical Chinese poems consist of one or two characters (Yi, Li, and Sun 2016) and for the similar reason, we use BLEU-3 and BLEU-4 to evaluate Obama speech generation performance. In our work, we use the whole test set as the references instead of trying to find some references for the following line given the previous line (He, Zhou, and Jiang 2012). The reason is in generation tasks we only provide some positive examples and then let the model catch the patterns of them and generate new ones. In addition to BLEU, we also choose poem generation as a case for human judgement since a poem is a creative text construction and human evaluation is ideal. Specifically, we mix the 20 real poems and 20 each generated from SeqGAN and MLE. Then 70 experts on Chinese poems are invited to judge whether each of the 60 poem is created by human or machines. Once regarded to be real, it gets + 1 score, otherwise 0. Finally, the average score for each algorithm is calculated.

The experiment results are shown in Tables 2 and 3, from which we can see the significant advantage of SeqGAN over the MLE in text generation. Particularly, for poem composition, SeqGAN performs comparably to real human data.

{|class="wikitable" style="border:1px solid black;border-spacing:1px; text-align:center; background-color:white; margin:1em auto; width:90%" |- !Algorithm !! Human score !! p-value !! BLEU-2 !! p-value |- !MLE |0.4165 |rowspan="2"|0.0034 |0.6670 |rowspan="2"|$< 10^6$ |- !SeqGAN |0.5356 | 0.7389 |- !Real data | 0.6011|| ||0.746|| |- |+ align="bottom" style="caption-side:top; text-align:left; font-weight:normal"|Table 2: Chinese poem generation performance comparison. |}

{|class="wikitable" style="border:1px solid black;border-spacing:1px; text-align:center; background-color:white; margin:1em auto; width:90%" |- !Algorithm !! BLEU-3 !! p-value !! BLEU-4 !! p-value |- !MLE |0.519 |rowspan="2"|$< 10^6$ |0.416 |rowspan="2"|0.00014 |- !SeqGAN |0.556 |0.427 |- |+ align="bottom" style="caption-side:top; text-align:left; font-weight:normal"|Table 3: Obama political speech generation performance. |}

Music Generation

For music composition, we use Nottingham dataset[7] as our training data, which is a collection of 695 music of folk tunes in midi file format. We study the solo track of each music. In our work, we use 88 numbers to represent 88 pitches, which correspond to the 88 keys on the piano. With the pitch sampling for every 0.4s[8], we transform the midi files into sequences of numbers from 1 to 88 with the length 32.

To model the fitness of the discrete piano key patterns, BLEU is used as the evaluation metric. To model the fitness of the continuous pitch data patterns, the mean squared error (MSE) (Manaris et al. 2007) is used for evaluation.

From Table 4, we see that SeqGAN outperforms the MLE significantly in both metrics in the music generation task.

{|class="wikitable" style="border:1px solid black;border-spacing:1px; text-align:center; background-color:white; margin:1em auto; width:90%" |- !Algorithm !! BLEU-4 !! p-value !! MSE !! p-value |- !MLE | 0.9210 |rowspan="2"|$< 10^{−6}$ |22.38 |rowspan="2"|0.00034 |- !SeqGAN | 0.9406 | 20.62 |- |+ align="bottom" style="caption-side:top; text-align:left; font-weight:normal"|Table 4: Music generation performance comparison. |}

Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed a sequence generation method, SeqGAN, to effectively train generative adversarial nets for structured sequences generation via policy gradient. To our best knowledge, this is the first work extending GANs to generate sequences of discrete tokens. In our synthetic data experiments, we used an oracle evaluation mechanism to explicitly illustrate the superiority of SeqGAN over strong baselines. For three real-world scenarios, i.e., poems, speech language and music generation, SeqGAN showed excellent performance on generating the creative sequences. We also performed a set of experiments to investigate the robustness and stability of training SeqGAN. For future work, we plan to build Monte Carlo tree search and value network (Silver et al. 2016) to improve action decision making for large scale data and in the case of longer-term planning.

Footnotes

- ↑ https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05473

- ↑ In our work, the generated sequence has a fixed length $T$, but note that CNN is also capable of the variable-length sequence discrimination with the max-over-time pooling technique (Kim 2014).

- ↑ Experiment code: https://github.com/LantaoYu/SeqGAN

- ↑ Implementation details are in the supplementary material.

- ↑ http://homepages.inf.ed.ac.uk/mlap/Data/EMNLP14/

- ↑ https://github.com/samim23/obama-rnn

- ↑ http://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~lisa/deep/data

- ↑ http://deeplearning.net/tutorial/rmnrbm.html

References

2016a

- (Bahdanau et al., 2016) ⇒ Bahdanau, D.; Brakel, P.; Xu, K.; et al. 2016. An actor-critic algorithm for sequence prediction. arXiv: 1607.07086.

2016b

- (Goodfellow, 2016) ⇒ Goodfellow, I. 2016. Generative adversarial networks for text. http://goo.gl1/Wg9DR7.

2016c

- (Goodfellow et al., 2016) ⇒ Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; and Courville, A. 2016. Deep learning. 2015.

2016d

- (Silver et al., 2016) ⇒ Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C. J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; et al. 2016. Mastering the game of go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529(7587):484-489.

2016e

- (Yi et al., 2016) ⇒ Yi, X.; Li, R.; and Sun, M. 2016. Generating chinese classical poems with RNN encoder-decoder. arXiv: 1604.01537.

2015a

- (Bachman & Precup, 2015) ⇒ Bachman, P., and Precup, D. 2015. Data generation as sequential decision making. In NJPS, 3249-3257.

2015b

- (Bengio et al., 2015) ⇒ Bengio, S.; Vinyals, O.; Jaitly, N.; and Shazeer, N. 2015. Scheduled sampling for sequence prediction with recurrent neural networks. In NIPS, 1171-1179.

2015c

- (Denton et al., 2015) ⇒ Denton, E. L.; Chintala, S.; Fergus, R.; et al. 2015. Deep generative image models using a laplacian pyramid of adversarial networks. In NIPS, 1486-1494.

2015d

- (Huszar, 2015) ⇒ Huszar, F. 2015. How (not) to train your generative model: Scheduled sampling, likelihood, adversary? arXiv: 1511.05101.

2015e

- (Lai et al., 2015) ⇒ Lai, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, K.; and Zhao, J. 2015. Recurrent convolutional neural networks for text classification. In AAA, 2267-2273.

2015f

- (Srivastava et al., 2015) ⇒ Srivastava, R. K.; Greff, K.; and Schmidhuber, J. 2015. Highway networks. arXiv: 1505.00387.

2015g

- (Wen et al., 2015) ⇒ Wen, T.-H.; Gasic, M.; Mrksic, N.; Su, P.-H.; Vandyke, D.; and Young, S. 2015. Semantically conditioned LSTM-based natural language generation for spoken dialogue systems. arXiv: 1508.01745.

2015h

- (Zhans & LeCun, 2015) ⇒ Zhang, X., and LeCun, Y. 2015. Text understanding from scratch. arXiv: 1502.01710.

2014a

- (Bahdanau et al., 2014) ⇒ Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; and Bengio, Y. 2014. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv: 1409.0473.

2014b

- (Cho et al., 2014) ⇒ Cho, K.; Van Merriénboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; et al. 2014. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. EMNLP.

2014c

- (Goodfellow et al., 2014) ⇒ Ian Goodfellow, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. (2014). “Generative Adversarial Nets.” In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

2014d

- (Kim, 2014) ⇒ Kim, Y. 2014. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv: 1408.5882.

2014e

- (Kingma & Welling, 2014) ⇒ Kingma, D. P., and Welling, M. 2014. Auto-encoding variational bayes. ICLR.

2014f

- (Srisvastava,2014) ⇒ Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G. E.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; and Salakhutdinov, R. 2014. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. JMLR 15(1):1929-1958.

2014g

- (Sutskever et al., 2014) ⇒ Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; and Le, Q. V. 2014. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In N/PS, 3104-3112.

2014h

- (Zhang & Lapata, 2014) ⇒ Zhang, X., and Lapata, M. 2014. Chinese poetry generation with recurrent neural networks. In EMNLP, 670-680.

2013a

- (Bengio et al., 2013) ⇒ Bengio, Y.; Yao, L.; Alain, G.; and Vincent, P. 2013. Generalized denoising auto-encoders as generative models. In NIPS, 899-907.

2013b

- (Graves, 2013) ⇒ Graves, A. 2013. Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks. arXiv: 1308.0850.

2013c

- (Vesely et al., 2013) ⇒ Vesely, K.; Ghoshal, A.; Burget, L.; and Povey, D. 2013. Sequence discriminative training of deep neural networks. In INTERSPEECH, 2345-2349.

2012a

- (Browne et al., 2012) ⇒ Browne, C. B.; Powley, E.; Whitehouse, D.; Lucas, S. M.; et al. 2012. A survey of monte carlo tree search methods. IEEE TCIAIG 4(1):1-43.

2012b

- (He et al., 2012) ⇒ He, J.; Zhou, M.; and Jiang, L. 2012. Generating chinese classical poems with statistical machine translation models. In AAAI.

2009a

- (Salakhutdinov, 2009) ⇒ Salakhutdinov, R. 2009. Learning deep generative models. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Toronto.

2009b

- (Hingston, 2009) ⇒ Hingston, P. 2009. A turing test for computer game bots. JEEE TCIAIG 1(3):169-186.

2007

- (Manaris et al., 2007) ⇒ Manaris, B.; Roos, P.; Machado, P.; et al. 2007. A corpus-based hybrid approach to music analysis and composition. In NCAI, volume 22, 839.

2006

- (Hinton et al., 2006) ⇒ Hinton, G. E.; Osindero, S.; and Teh, Y.-W. 2006. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural computation 18(7):1527- 1554.

2002

- (Papineni et al., 2002) ⇒ Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; and Zhu, W.-J. 2002. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In ACL, 311-318.

1999

- (Sutton et al., 1999) ⇒ Sutton, R. S.; McAllester, D. A.; Singh, S. P.; Mansour, Y.; et al. 1999. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. In NJPS, 1057-1063.

1997

- (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997) ⇒ Hochreiter, S., and Schmidhuber, J. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 9(8):1735—1780.

1996

- (Quinlan, 1996) ⇒ Quinlan, J. R. 1996. Bagging, boosting, and c4. 5. In AAAIIAAT, Vol. 1, 725-730.

1992

- (Williams, 1992) ⇒ Williams, R. J. 1992. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Machine learning 8(3-4):229-256.

1990

- (Glynn, 1990) ⇒ Glynn, P. W. 1990. Likelihood ratio gradient estimation for stochastic systems. Communications of the ACM 33(10):75-84.

BibTeX

@inproceedings{2017_SeqGANSequenceGenerativeAdversa,

author = {Lantao Yu and

Weinan Zhang and

Jun Wang and

Yong Yu},

editor = {Satinder P. Singh and

Shaul Markovitch},

title = {SeqGAN: Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets with Policy Gradient},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2017),

February 4-9, 2017, San Francisco, California, USA},

pages = {2852--2858},

publisher = {AAAI Press},

year = {2017},

url = {http://aaai.org/ocs/index.php/AAAI/AAAI17/paper/view/14344},

}

| Author | volume | Date Value | title | type | journal | titleUrl | doi | note | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 SeqGANSequenceGenerativeAdversa | Yong Yu Weinan Zhang Jun Wang Lantao Yu | SeqGAN: Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets with Policy Gradient | 2017 |